For the past few years I've spent most of my days in the Peruvian Amazon, usually WiFi-less standing in the rain or staring so hard into the center of the plants that I become them. While I find myself deepening my relationship to the elements of the forest, I also find myself growing father away from my very own country, landscapes and people.

More than once, I've had someone say to me "if you want to make a change, you should do something in your neighborhood!" Point taken. Ivan Illich put it well in a cutting speech titled "To Hell with Good Intentions" addressed to young Americans embarking on community service adventures in 'developing' countries:

"You start on your task without any training. Even the Peace Corps spends around $10,000 on each corps member to help him adapt to his new environment and to guard him against culture shock. How odd that nobody ever thought about spending money to educate poor Mexicans in order to prevent them from the culture shock of meeting you?"

Too often, volunteers working at American/European NGOs rock up in foreign countries with the intention of "helping" without any real idea of what needs to be done. I remember volunteering in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2007. Creole and African-American communities in the Lower Ninth Ward who were disproportionately impacted by the storm found themselves living in devastating conditions with limited access to food and water for years. I was canvassing (surveying) the area, asking what people's most immediate needs were. A tired woman told me "they [NGOs] keep giving us fences when we need roofs."

This reminds me of what the Australian aboriginal activist Lila Watson said in response to missionaries coming to 'help':

"If you have come to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up in mine, then let us walk together..."

The more often I switch between living and working with Amazonian communities and my North American kin, the more I realize we are the ones that need 'help'. Depression, PTSD, addiction, eating disorders, anxiety - these nebulous yet pervasive illnesses are epidemic in the West. While, of course, there are exceptions, these conditions do not haunt those who live in tightly-knit communities in harmony and respect with their land with the same ferocity, ubiquity and persistence as they do in urban landscapes.

Unsurprisingly, psychedelics are proven to increase feelings of nature relatedness, which certainly helps to explain their evergreen presence and use by indigenous peoples across the world. The more that we, scientists and researchers explore the field of psychedelics, the more we realize there is so very much to learn.

This is where bridge-building comes in; the work of translating and uniting different worldviews and approaches to synergize new, holistic ways of seeing and being. In biology, we find a concept called the edge effect or ecotone. The edge effect is a term used to describe the place where distinct ecosystems meet. They're territories of confrontation, chaos, clashing. They're also territories of innovation, synergy, and even sites for the emergence of new species! Now think of this edge concept as an analogy for cultural cross-pollination and globalization. I, like many others, work in this space between indigenous and mixed, botanical and technological, romantic and practical, imaginary and empirical. These are contemporary edge zones.

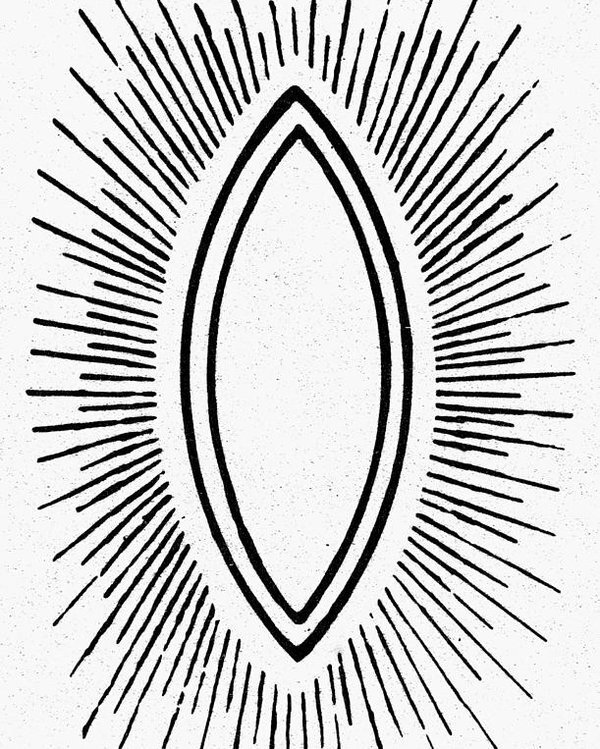

The edge effect is expressed in mathematics as a shape called the vescia piscis - the intersection of two disks with the same radius. I learned about this years ago when I was eating formidable doses of LSD and studying sacred geometry. This shape holds significance for esoteric traditions and in Early Christian art, representing a sacred unity and meeting point. It is from this linking of two discrete circles that life multiplies (think of a zygote growing) and evolves into grander, more complex geometrical expressions of itself. It also looks quite a bit like the human portal into life ;)

Between traveling across the US with Head Talks educating audiences about plant medicines and indigenous epistemology (methods of knowledge-production) and doing my naked rain dance in the jungle, I find my appreciation for this concept/shape deepening and guiding my work. While I'm one of 'those guys' working with an NGO (The Chaikuni Institute, an amazing intercultural project in the Peruvian forest) it's very clear that solidarity isn't a one way street - foreigners, locals, indigenous folk and everyone involved are in a process of cross-pollination and mutual aid.

As we move beyond this model of 'helping' others in 'developing countries' or supporting justice work in any form, the wisdom of the edge can guide and sustain our actions. The edge/ecotone/vescia teaches us about interconnectedness and reciprocity, bridge building, world weaving. Our liberation will indeed be found through the mutual respect and love found in our edge-zones.