OP October 26, 2015

Yesterday I learned the oldest member of the Secoya tribe, Matilde Payaguaje, passed away. Her precise age was unknown, but she was believed to have been over one hundred years old. I wonder what life was like one hundred years ago at coordinates 0°58′26″S 75°11′49″W, in the far reaches of the Amazon rainforest.

The dwindling Secoya (or Siekopai) population of approximately 650 live in small multi-family plots of land along Rio Aguarico, in the Sucumbíos region of the Ecuadorian Amazon. The Secoya are classified as members of the Tucanoan ethno-linguistic group, along with the Sinoa, Coreguaje, and Macaguaje of Colombia, and the Maijuna and Tetete of Peru — all tribes who inhabit the area between the Napo and Putumayo Rivers. Like many communities indigenous to this region, demands from the paradigm of Western economic growth for commodities such as rubber, timber, ‘preciosities’ — and most recently palm oil and petroleum — has had woeful effects on nearly every aspect of their livelihood. From blunt force ethnocide and slavery to disease and forced acculturation, a devastating legacy of Occidential presence in the Amazon has effectively destroyed what was once a robust population, culture, and identity, and jungle.

I always thought calendars looked dissonant and displaced, nailed into the wooden planks of the stilted houses, hidden beneath tree canopies whose leaves often outsized the people living beneath them. Calendars, I thought, didn’t belong there. Time was a concept enforced by agenda makers and job takers from Northern lands, where I am from. Time was an imposter. Time seemed a tacky and irrelevant social structure, awkwardly inserted in an environment so dense with life and death.

Some people donned old, broken-faced watches on their wrists - yet I felt other notions of time-keeping prevailed amongst the Secoya. Eventually I learned rather than the linear, 60 minute, 24 hour, 12 month, 365 day to a year calendar, there are three seasons, perceived cyclically, in the traditional Secoya cosmovision. They are called Ometëkawe, Okotekawe, and Kakotekawe. The rest of the timekeeping is simply up to the sun.

+ Ometëkawe can be recognized when turtles bury their eggs in the shores of the rivers. It is also when the Orion’s belt is in the center of the sky or East, which indicates the best conditions to plant paihuea (corn), a’so (yucca), ñajo (tubers), and u’kuisi — a pearly seeded cardamom-like plant.

+ Okotekawe is the season that follows Ometëkawe, characterized by heavy rain. It is monkey hunting season.

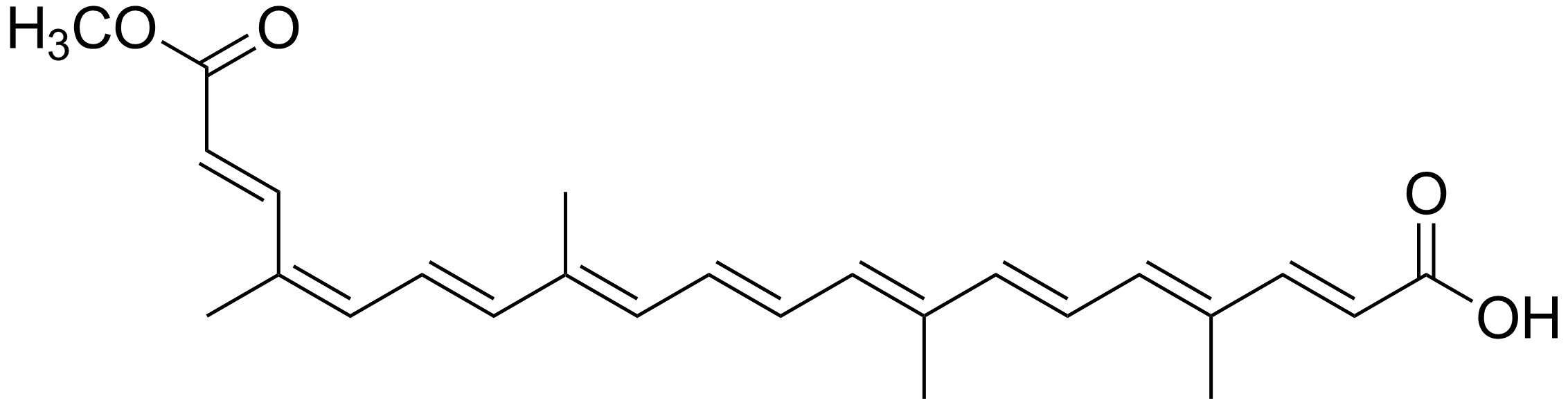

+ Kakotekawe is the ‘season of the cicadas,’ which coincides with what we call August, September, and October. The rainfall diminishes, once again the rivers become shallow — yielding favorable conditions for fishing. It is an auspicious time for inter-planetary communion with the celestial spirits, nañe siekopaï, mediated by the ritualized consumption of yagé.

I imagine Matilde also saw time as an anomaly. Her mere presence was a portal into the past — her life, a testimony to the unprecedented speed of global change.

In her one hundred years, Matilde saw the beginning and the end of many things. She saw the construction of asphalt roads swerving through her emerald green jungle like strange dark veins. Upon these roads traveled loud sixteen-wheeled creatures, with big silver barrels carrying black sludge that white cultures run on. Fossil fuels — a technological feat of time travel — digging into the geological archives of planet earth to feed a people with a different appetite for life. And along these roads, pipes carry this sludge, stretching into distant horizons. Electricity, packaged food, motorcycles. Ecuadorian soap operas, chewing gum, key chains (but no doors in the village yet), guns.